Introduction to Python Decorators

Have you ever found yourself writing the same piece of code, like logging function calls or measuring execution time, across multiple functions? It’s a common scenario that can lead to repetitive, hard-to-maintain code. What if there was a way to add this functionality *without* altering the original functions themselves?

What are Python Decorators?

This is where python decorators come to the rescue. At their core, python decorators are functions that modify or extend the behavior of other functions or classes without changing their original code (Source: DataCamp, PythonTips).

The “Why”: Benefits of Decorators

The primary advantages of using decorators are:

- Code Reusability: Avoids repeating the same logic in multiple places.

- Cleaner Syntax: Makes your code more readable and expressive.

- Separation of Concerns: Allows you to add cross-cutting concerns (like logging or authentication) without cluttering your core business logic.

- Functionality Extension: Adds new features to existing functions or classes with minimal effort.

They are a powerful tool for enhancing code maintainability and improving how you structure your Python applications.

What We’ll Cover

In this post, we’ll delve into the fascinating world of python decorators. We’ll explore their syntax, understand how python function decorators and python class decorators work, and look at practical applications with a comprehensive python decorator tutorial.

Understanding the `decorator syntax python`

The `@` Symbol: Your Gateway

The magic behind Python decorators is largely facilitated by a simple yet powerful symbol: the `@`.

The `@` symbol is the key to decorator syntax in Python (Source: Real Python). When you see `@decorator_name` placed directly above a function or class definition, it’s a concise way of applying that decorator.

Behind the Scenes: Syntactic Sugar

Think of the `@` syntax as syntactic sugar. What it appears to be is:

@simple_decorator

def greet():

print("Hello!")

Is actually equivalent to this more explicit form:

def greet():

print("Hello!")

greet = simple_decorator(greet)

(Source: Real Python, DataCamp).

This means the decorator, `simple_decorator` in this case, is called with the function `greet` as its argument. The decorator then returns a *new* function (often a wrapper function) which replaces the original `greet`.

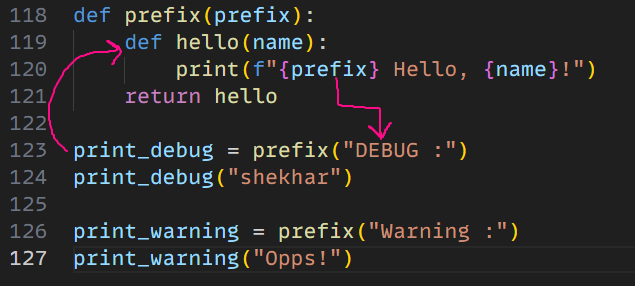

The Core Mechanism: Functions as First-Class Citizens

This elegant mechanism works because of a fundamental concept in Python: functions are first-class objects. This means:

- Functions can be assigned to variables.

- Functions can be passed as arguments to other functions.

- Functions can be returned from other functions.

(Source: Real Python, DataCamp).

A decorator, therefore, is essentially a function that takes another function as an argument and returns a new function. This returned function typically wraps the original function, adding behavior before, after, or around its execution.

Understanding this is key to mastering decorator syntax python.

Deep Dive into `python function decorators`

How Function Decorators Wrap

Function decorators work by wrapping the original function with additional behavior. They define an inner function (often called `wrapper`) that contains the logic to be executed before and after the original function call. The decorator then returns this `wrapper` function.

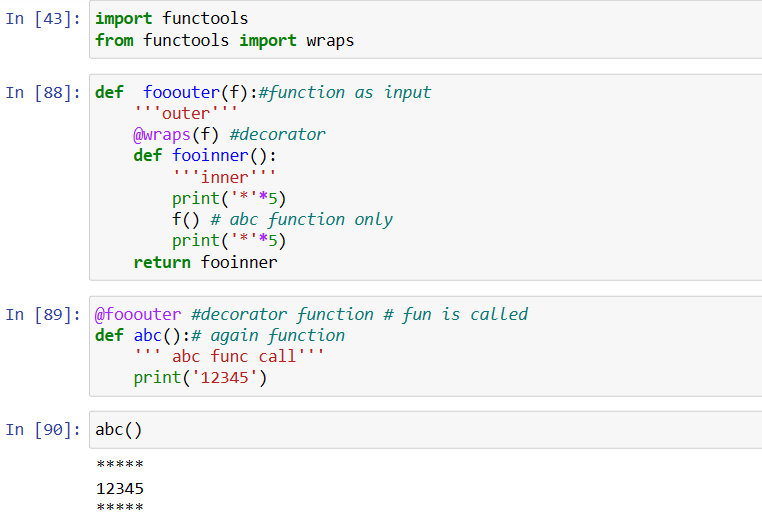

Here’s a simple, illustrative example:

import functools

def simple_decorator(func):

@functools.wraps(func) # Preserves metadata of the original function

def wrapper():

print("Before the function call...")

func() # Call the original function

print("After the function call...")

return wrapper

@simple_decorator

def greet():

print("Hello!")

greet()

Expected output:

Before the function call...

Hello!

After the function call...

Explanation of the Example

In the example above:

- The `simple_decorator` function takes `func` (which will be `greet`) as its argument.

- It defines an inner function called `wrapper`.

- Inside `wrapper`, we first print a message, then call the original function `func()`, and finally print another message.

- The `simple_decorator` returns the `wrapper` function.

- When `greet()` is called after being decorated, we are actually calling the `wrapper` function.

(Source: DataCamp, freeCodeCamp).

Notice the use of `@functools.wraps(func)`. This is crucial for preserving the metadata (like the function name and docstring) of the original function, which is good practice.

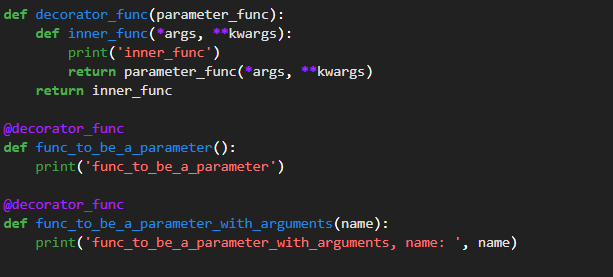

Handling Arbitrary Arguments (`*args`, `**kwargs`)

The previous example only works for functions that take no arguments. Most functions do, however, accept arguments. To make our decorators versatile, we need to handle arbitrary positional and keyword arguments.

This is where `*args` and `**kwargs` come into play. They allow the wrapper function to accept any number of positional arguments (collected into a tuple `args`) and any number of keyword arguments (collected into a dictionary `kwargs`).

Here’s the standard pattern:

import functools

def decorator_with_args(func):

@functools.wraps(func)

def wrapper_decorator(*args, **kwargs):

# Do something before the function call

print(f"Calling function {func.__name__} with args: {args}, kwargs: {kwargs}")

# Call the original function with its arguments

value = func(*args, **kwargs)

# Do something after the function call

print(f"Function {func.__name__} returned: {value}")

return value # Return the result of the original function

return wrapper_decorator

@decorator_with_args

def multiply(x, y):

return x * y

result = multiply(5, 3)

print(f"Final result: {result}")

@decorator_with_args

def greet_person(name, greeting="Hello"):

return f"{greeting}, {name}!"

message = greet_person("Alice", greeting="Hi")

print(f"Final message: {message}")

Expected output:

Calling function multiply with args: (5, 3), kwargs: {}

Function multiply returned: 15

Final result: 15

Calling function greet_person with args: ('Alice',), kwargs: {'greeting': 'Hi'}

Function greet_person returned: Hi, Alice!

Final message: Hi, Alice!

By using `*args` and `**kwargs`, our decorator can now be applied to virtually any function, regardless of its signature. This makes python function decorators incredibly flexible (Source: Real Python).

Common Use Cases for Function Decorators

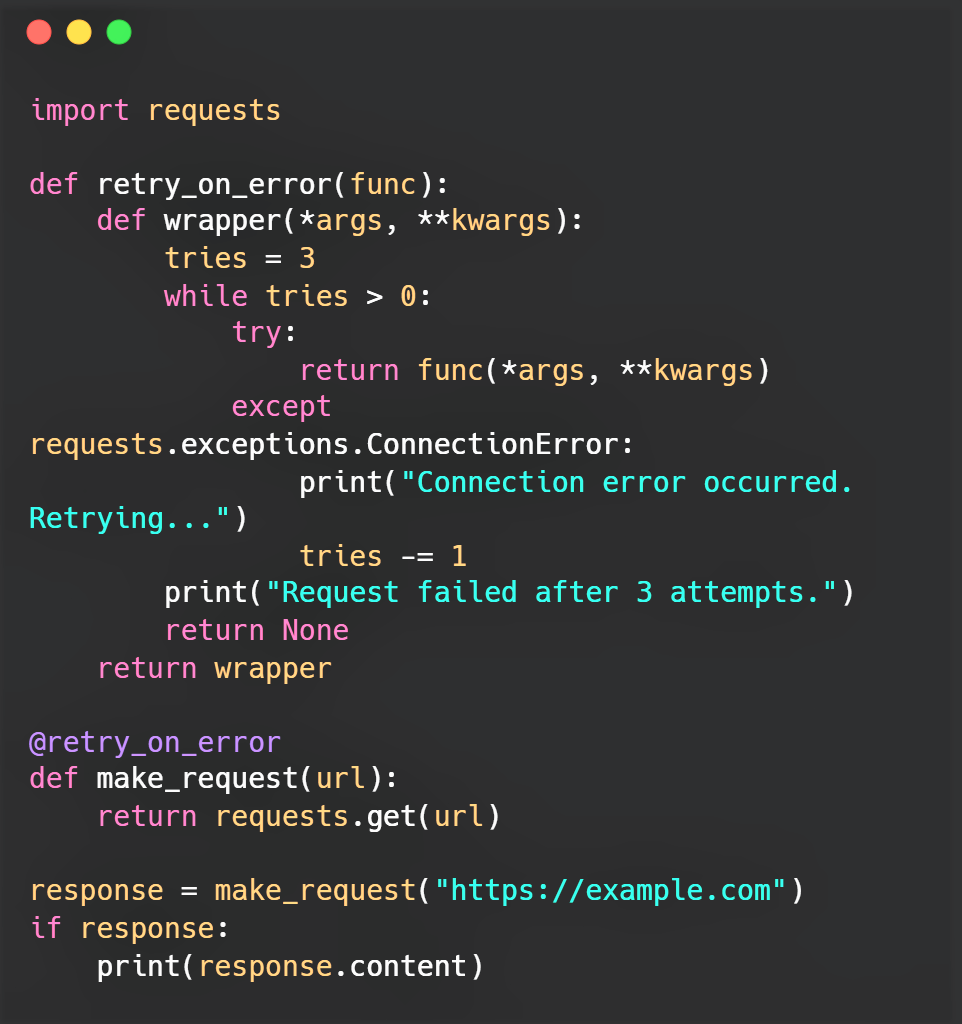

The flexibility of function decorators makes them suitable for a wide range of tasks:

- Logging: Record function calls, their arguments, and return values. This is invaluable for debugging and monitoring applications.

- Access Control/Authorization: Decorators can check user permissions or roles before allowing a function to execute, ensuring that only authorized users can perform certain actions.

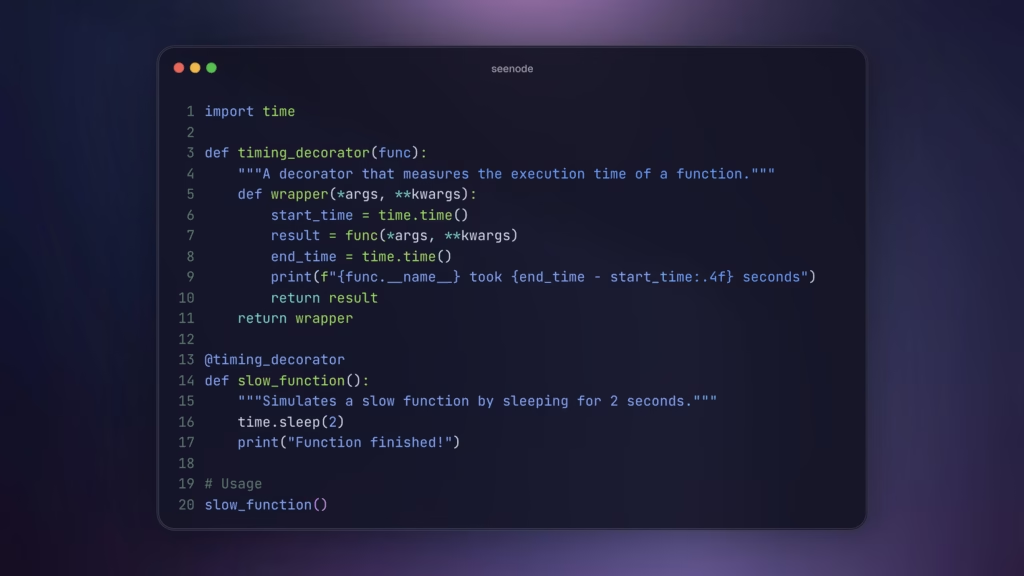

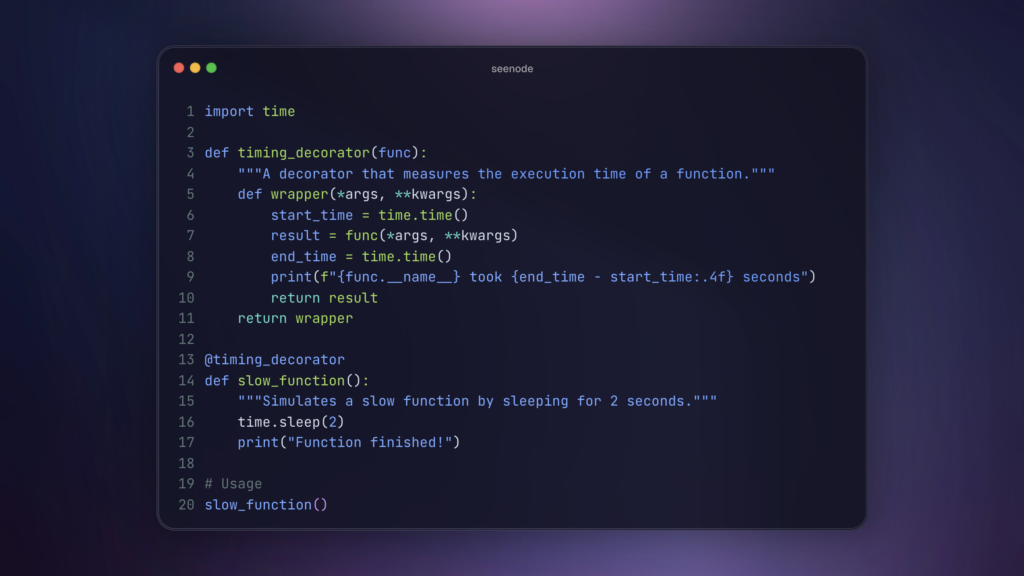

- Performance Measurement/Timing: As explored in research, a timing decorator can precisely measure how long a function takes to run. This is essential for identifying performance bottlenecks. The following snippet shows a conceptual example using `time.perf_counter`:

import time import functools def timer(func): @functools.wraps(func) def wrapper_timer(*args, **kwargs): start_time = time.perf_counter() value = func(*args, **kwargs) end_time = time.perf_counter() run_time = end_time - start_time print(f"Function {func.__name__} took {run_time:.4f} seconds") return value return timer - Input Validation: Decorators can validate the arguments passed to a function, ensuring they meet certain criteria (e.g., correct type, within a range) before the function logic even begins.

- Modifying Return Values: A decorator can intercept the return value of a function and transform it. For instance, a decorator could ensure that the output of a string-manipulating function is always converted to uppercase.

import functools def uppercase_return(func): @functools.wraps(func) def wrapper(*args, **kwargs): result = func(*args, **kwargs) if isinstance(result, str): return result.upper() return result return wrapper @uppercase_return def greet_lower(name): return f"hello, {name}" print(greet_lower("Bob")) # Output: HELLO, BOB

These examples highlight the power and utility of python function decorators in building robust and efficient applications.

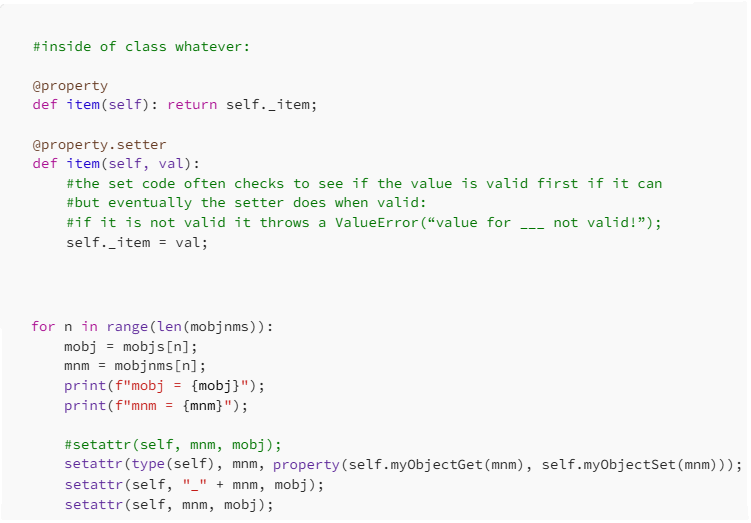

Exploring `python class decorators`

Introduction to Class Decorators

While function decorators are very common, Python also allows you to use classes as decorators. Class decorators offer an alternative approach, often leveraging the `__call__` method to make instances of the decorator class callable.

Essentially, when you apply a class decorator using the `@` syntax, Python creates an instance of that class, passing the decorated function or class to the decorator’s `__init__` method. If the decorated item is then called, the class’s `__call__` method is executed.

Example of a Class Decorator

Let’s revisit the uppercase transformation example, but this time using a class decorator:

import functools

class UppercaseDecorator:

def __init__(self, function):

# Store the original function

self.function = function

def __call__(self, *args, **kwargs):

# This method is called when the decorated function is invoked

result = self.function(*args, **kwargs) # Call the original function

# Apply the transformation

if isinstance(result, str):

return result.upper()

return result

@UppercaseDecorator

def greet():

return "hello there"

@UppercaseDecorator

def get_name(first_name, last_name):

return f"{first_name} {last_name}"

print(greet())

print(get_name("Jane", "Doe"))

Expected output:

HELLO THERE

JANE DOE

Mechanism Explanation

Here’s how it works:

- When `@UppercaseDecorator` is placed above `def greet():`, Python calls `UppercaseDecorator(greet)`.

- The `__init__` method of `UppercaseDecorator` is executed, receiving `greet` as the `function` argument. It stores this function in `self.function`.

- The name `greet` is now bound to the *instance* of `UppercaseDecorator` created.

- When `greet()` is called, it’s actually invoking the `__call__` method of the `UppercaseDecorator` instance.

- Inside `__call__`, `self.function(*args, **kwargs)` executes the original `greet` function.

- The result is then transformed (uppercased if it’s a string) before being returned.

(Source: DataCamp).

When to Use Class Decorators

Class decorators offer distinct advantages in certain scenarios:

- Maintaining State: If your decorator needs to maintain state across multiple calls (e.g., a counter for how many times a function has been called), a class decorator is a natural fit because you can store this state as instance attributes.

- Storing Configuration: Similar to state, decorators that require configuration or settings can benefit from being classes, storing these as attributes.

- Implementing Complex Logic: For decorators with multiple methods or more intricate logic, a class structure can provide better organization and readability.

- Decorator Factories: When decorators themselves need to accept arguments (which we’ll cover next), classes can sometimes offer a cleaner structure than nested functions.

While function decorators are often sufficient for simple tasks, python class decorators provide a more object-oriented and stateful approach when needed (Source: DataCamp).

Advanced Concepts and Best Practices

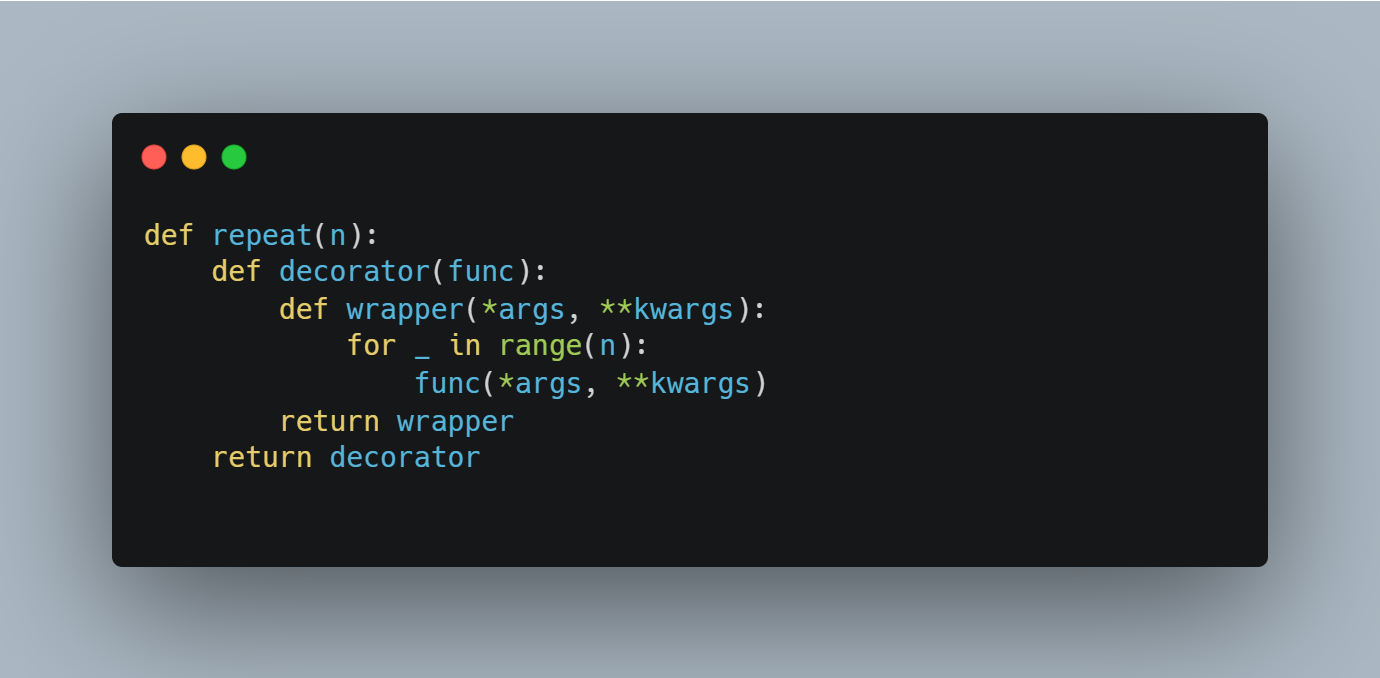

Decorators with Arguments

So far, we’ve looked at decorators that are applied directly. But what if you want to pass arguments to the decorator itself? For example, a decorator that repeats a function’s execution a specified number of times.

To achieve this, we need an extra layer of nesting. The outermost function will accept the decorator’s arguments and return the actual decorator function.

Consider this `repeat` decorator:

import functools

def repeat(num_times): # Outer function accepts decorator arguments

def decorator_repeat(func): # This is the actual decorator

@functools.wraps(func) # This is the wrapper

def wrapper_repeat(*args, **kwargs):

for _ in range(num_times):

value = func(*args, **kwargs)

return value

return wrapper_repeat

return decorator_repeat

@repeat(num_times=3) # Passing 'num_times=3' to the outer function

def say_hello():

print("Hello!")

say_hello()

Expected output:

Hello!

Hello!

Hello!

In this pattern:

- `repeat(num_times=3)` is called first, returning `decorator_repeat`.

- `decorator_repeat` then receives `say_hello` and returns `wrapper_repeat`.

- `say_hello` is now `wrapper_repeat`, which executes the original `say_hello` three times.

(Source: Real Python).

Chaining Multiple Decorators

You can apply multiple decorators to a single function by stacking them one above the other:

import functools

def make_bold(func):

@functools.wraps(func)

def wrapper(*args, **kwargs):

return f"{func(*args, **kwargs)}"

return wrapper

def make_italic(func):

@functools.wraps(func)

def wrapper(*args, **kwargs):

return f"{func(*args, **kwargs)}"

return wrapper

@make_bold

@make_italic

def say_hello():

return "hello"

print(say_hello())

Expected output:

hello

Crucially, the order of decorators matters significantly. They are applied from bottom to top. In the example above, `make_italic` is applied first, and then `make_bold` wraps the result of `make_italic`. If you swapped them:

@make_italic

@make_bold

def say_hello_reversed_order():

return "hello"

print(say_hello_reversed_order())

The output would be `hello`.

(Source: Real Python).

Preserving Function Metadata (`functools.wraps`)

As touched upon earlier, decorators replace the original function with a wrapper function. This can cause issues because the wrapper function has its own name, docstring, and other metadata, obscuring the original function’s identity. This is problematic for introspection, debugging, and documentation tools.

The solution is `functools.wraps`. By applying `@functools.wraps(func)` to your wrapper function, you instruct Python to copy the metadata from the original function (`func`) to the wrapper. This ensures that tools and developers can still access the original function’s name (`__name__`), docstring (`__doc__`), etc.

It’s a small addition that makes a big difference in maintainability and usability. Therefore, using `@functools.wraps` is a best practice for all decorators (Source: Real Python).

When *Not* to Use Decorators

While powerful, decorators aren’t always the right tool for every job. Consider these points:

- Simplicity: If the added logic is very simple and only used in one place, inlining it might be clearer than creating a decorator.

- Readability: If a decorator makes the flow of execution significantly harder to follow, it might be counterproductive.

- Over-Engineering: Applying decorators for very minor enhancements or when the decorator is only used once can be unnecessary.

- Complexity: Chaining many decorators or using decorators with arguments can sometimes introduce complexity that outweighs the benefits.

The key is to use decorators judiciously. They are best employed for reusable, cross-cutting concerns that enhance the core functionality without becoming a burden themselves. Remember that overuse can lead to confusion.

Practical `python decorator tutorial`: Putting it all together

Real-World Example: A Combined Timer and Logger

Let’s combine the concepts of timing and logging into a single, robust decorator. This is a common pattern seen in many applications, providing valuable insights into function performance and execution flow.

import functools

import time

import logging

# Configure basic logging

logging.basicConfig(level=logging.INFO, format='%(asctime)s - %(levelname)s - %(message)s')

def timer_logger(func):

"""Decorator that measures function execution time and logs calls."""

@functools.wraps(func)

def wrapper_timer_logger(*args, **kwargs):

# Log the function call with arguments

logging.info(f"Calling function '{func.__name__}' with args: {args}, kwargs: {kwargs}")

start_time = time.perf_counter()

try:

# Execute the original function

result = func(*args, **kwargs)

end_time = time.perf_counter()

run_time = end_time - start_time

# Log successful execution and duration

logging.info(f"Function '{func.__name__}' completed successfully in {run_time:.4f} seconds. Returned: {result}")

return result

except Exception as e:

# Log any exceptions that occur

end_time = time.perf_counter()

run_time = end_time - start_time

logging.error(f"Function '{func.__name__}' raised an exception: {e} after {run_time:.4f} seconds.")

raise # Re-raise the exception to maintain original behavior

return wrapper_timer_logger

@timer_logger

def calculate_sum(n):

"""Calculate sum of numbers from 1 to n."""

if not isinstance(n, int) or n < 0:

raise ValueError("Input must be a non-negative integer.")

total = sum(range(1, n + 1))

# Simulate some work

time.sleep(0.1)

return total

@timer_logger

def greet_user(name="Guest"):

"""Greets a user."""

return f"Hello, {name}!"

# --- Demonstrating the decorator ---

print("--- Testing calculate_sum ---")

try:

sum_result = calculate_sum(1000000)

print(f"Sum calculated: {sum_result}")

except ValueError as ve:

print(f"Error: {ve}")

print("\n--- Testing greet_user ---")

message_guest = greet_user()

print(f"Greeting: {message_guest}")

message_user = greet_user("Alice")

print(f"Greeting: {message_user}")

print("\n--- Testing error handling ---")

try:

calculate_sum(-5)

except ValueError as ve:

print(f"Caught expected error: {ve}")

Expected output snippet (timestamps will vary):

--- Testing calculate_sum ---

2023-10-27 10:00:00,123 - INFO - Calling function 'calculate_sum' with args: (1000000,), kwargs: {}.

2023-10-27 10:00:00,225 - INFO - Function 'calculate_sum' completed successfully in 0.1015 seconds. Returned: 500000500000

Sum calculated: 500000500000

--- Testing greet_user ---

2023-10-27 10:00:00,226 - INFO - Calling function 'greet_user' with args: (), kwargs: {}.

2023-10-27 10:00:00,227 - INFO - Function 'greet_user' completed successfully in 0.0005 seconds. Returned: Hello, Guest!

Greeting: Hello, Guest!

2023-10-27 10:00:00,227 - INFO - Calling function 'greet_user' with args: (), kwargs: {'name': 'Alice'}.

2023-10-27 10:00:00,228 - INFO - Function 'greet_user' completed successfully in 0.0004 seconds. Returned: Hello, Alice!

Greeting: Hello, Alice!

--- Testing error handling ---

2023-10-27 10:00:00,228 - INFO - Calling function 'calculate_sum' with args: (-5,), kwargs: {}.

2023-10-27 10:00:00,229 - ERROR - Function 'calculate_sum' raised an exception: Input must be a non-negative integer. after 0.0005 seconds.

Caught expected error: Input must be a non-negative integer.

Detailed Walkthrough

- Purpose: The `timer_logger` decorator aims to log when a function is called, with what arguments, how long it takes, what it returns, and crucially, if it raises an error.

- Metadata Preservation: `@functools.wraps(func)` ensures that the `wrapper_timer_logger` function retains the original function's metadata (like `__name__` and `__doc__`).

- Timing Mechanism: `time.perf_counter()` is used to get high-resolution timestamps before and after the function `func` is called. The difference gives the precise execution `run_time`.

- Argument Handling: `*args` and `**kwargs` are used in `wrapper_timer_logger` to accept any arguments passed to the decorated function, making the decorator universally applicable.

- Logging: The `logging` module is used to record messages. We log the call, the successful completion with duration and result, or any exceptions encountered.

- Error Handling: A `try...except...raise` block is used to catch potential exceptions from the original function. This allows us to log the error *and* re-raise it, so the calling code still receives the exception as expected.

- Applying the Decorator: The `@timer_logger` syntax elegantly applies this complex behavior to `calculate_sum` and `greet_user` without modifying their internal logic.

- Execution Flow: When `calculate_sum(1000000)` is called, the `wrapper_timer_logger` executes, logs the call, starts the timer, calls the *actual* `calculate_sum` logic, stops the timer, logs the result and duration, and then returns the computed sum. The same applies to `greet_user`.

This integrated example demonstrates how decorators can encapsulate complex, reusable functionality, leading to cleaner and more observable code, as shown in this practical python decorator tutorial.

Conclusion

Recap: What We've Learned

We've journeyed through the essential aspects of python decorators. We learned that they are a powerful design pattern for extending or modifying the behavior of functions and classes without altering their source code. We explored the clean `decorator syntax python` using the `@` symbol and understood how it works under the hood as syntactic sugar for function reassignment.

We took a deep dive into `python function decorators`, understanding how they wrap functions and how to handle arbitrary arguments using `*args` and `**kwargs`. We also distinguished them from `python class decorators`, which are useful for decorators that need to maintain state or implement more complex logic via the `__call__` method.

Reiterating the Advantages

The primary benefits of embracing decorators are clear: significantly improved code reusability, a cleaner and more readable codebase, and effective separation of concerns. They allow you to elegantly handle cross-cutting concerns like logging, timing, authentication, and more, keeping your core business logic focused and uncluttered.

Putting it into Practice

The best way to truly grasp decorators is to experiment. Start by implementing simple decorators for tasks like logging function calls or basic input validation in your own projects. As you become more comfortable, explore more advanced patterns, such as decorators with arguments and chaining multiple decorators. Mastering decorators is a significant step towards writing more elegant, maintainable, and Pythonic code.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the main purpose of a Python decorator?

The main purpose of a Python decorator is to modify or enhance the behavior of a function or class without permanently altering its original code. It allows for the addition of functionality like logging, timing, access control, or data validation in a reusable and non-intrusive way.

Can a decorator take arguments?

Yes, a decorator can take arguments. This is typically achieved by creating an outer function that accepts the decorator's arguments and returns the actual decorator function. This results in an additional layer of nesting.

Why is `functools.wraps` important?

The `functools.wraps` decorator is important because it copies the metadata (such as the function name, docstring, and annotations) from the original wrapped function to the wrapper function. Without it, debugging and introspection tools might show information about the wrapper instead of the original function, making the code harder to understand and work with.

What is the difference between function and class decorators?

Function decorators are typically simpler and consist of nested functions where an outer function takes the decorated function and returns a wrapper. Class decorators use a class, often implementing `__init__` to store the decorated function and `__call__` to execute the wrapped logic. Class decorators are more suitable when the decorator needs to maintain state or implement more complex logic.

How do decorators handle functions with different arguments?

Decorators handle functions with different arguments by using `*args` and `**kwargs` in the wrapper function. `*args` collects any positional arguments passed to the decorated function into a tuple, and `**kwargs` collects any keyword arguments into a dictionary. These collected arguments are then passed on to the original function when it's called within the wrapper.