“`html

Unlocking Elegance: A Comprehensive Guide to Python Decorators

Estimated reading time: 15 minutes

Key Takeaways

- Python decorators are a powerful feature that allow you to modify or enhance functions and methods in a clean and reusable way, adhering to the DRY principle.

- They are essentially functions that wrap other functions, adding functionality before or after the original function’s execution without altering its source code.

- The `@` symbol is syntactic sugar for applying decorators, making the code more readable and Pythonic.

- Common use cases include logging, access control, input validation, caching, and timing.

- Both function and class decorators exist, each serving distinct purposes in modifying behavior.

- Understanding the order of execution when stacking multiple decorators is crucial for predictable behavior.

Table of Contents

Introduction

Imagine a world where you could effortlessly sprinkle extra functionality onto your Python functions and methods without touching their original code. This isn’t a distant dream; it’s the reality offered by Python decorators. These elegant constructs empower developers to modify or extend the behavior of functions and methods in a clean, reusable, and highly maintainable way. By adhering to the DRY (Don’t Repeat Yourself) principle, decorators help keep your codebase tidy and focused.

At their core, Python decorators are functions that accept another function as an argument, add some form of functionality, and then return another function. This might sound a bit abstract at first, but the practical applications are vast. Whether you need to implement sophisticated logging, enforce access control, measure execution times, or validate inputs, decorators provide a standardized and Pythonic solution. (Source: DataCamp, Python Tips)

Common use cases for decorators include:

- Logging: Recording function calls and their arguments.

- Access Control: Checking user permissions before executing a function.

- Timing: Measuring how long a function takes to run.

- Input Validation: Ensuring function arguments meet certain criteria.

(Source: Dev.to)

This comprehensive Python decorator tutorial will guide you through the intricacies of both function and class decorators, equipping you with the knowledge to harness their full potential in your Python projects. The primary keyword we’ll be exploring is, of course, python decorators.

What Are Python Decorators?

To truly grasp decorators, we first need to understand a fundamental concept in Python: functions as first-class objects. In Python, functions aren’t just lines of code; they are treated like any other variable. This means you can:

- Assign them to variables.

- Pass them as arguments to other functions.

- Return them from other functions.

This ability to treat functions as data is what allows for the creation of higher-order functions. A higher-order function is simply a function that either takes one or more functions as arguments or returns a function as its result, or both. Decorators are a prime example of this concept in action. (Source: freeCodeCamp)

Now, let’s talk about the syntax. You’ve likely seen the enchanting @ symbol preceding a function definition. This symbol is not magic; it’s known as decorator syntax python, and it’s a form of syntactic sugar designed to make applying decorators much cleaner.

Consider this:

@my_decorator

def my_function():

pass

This is syntactic sugar for the following more verbose equivalent:

def my_function():

pass

my_function = my_decorator(my_function)

(Source: Dev.to)

Essentially, the @decorator_name syntax tells Python to pass the function defined immediately below it as an argument to the decorator_name function. The return value of the decorator function then replaces the original function. This is the core mechanism behind how python decorators work.

Python Function Decorators

The most common type of decorator you’ll encounter is the python function decorator. These decorators are functions designed to wrap other functions, adding behavior without modifying the original function’s code.

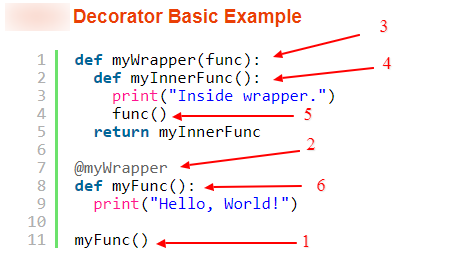

Let’s break down the basic structure of a python function decorator:

- The Decorator Function: This is the outer function. It accepts the original function (let’s call it

func) as its sole argument. - The Wrapper Function: Inside the decorator function, you define another function, often called

wrapper. This inner function is where the added logic resides. It will execute *before* and/or *after* calling the original function. - Handling Arguments: The wrapper function must be capable of accepting any arguments that the original function might take. This is achieved using

*args(for positional arguments) and**kwargs(for keyword arguments). - Returning the Wrapper: The decorator function’s job is to return the wrapper function. This returned wrapper function is what will be called when the decorated function is invoked.

Here’s a simple example illustrating this structure:

def my_simple_decorator(func):

def wrapper(*args, **kwargs):

print("Something is happening before the function is called.")

result = func(*args, **kwargs)

print("Something is happening after the function is called.")

return result

return wrapper

@my_simple_decorator

def say_hello(name):

print(f"Hello, {name}!")

say_hello("Alice")

When you run the code above:

- The

say_hellofunction is passed tomy_simple_decorator. my_simple_decoratordefines and returns thewrapperfunction.- The name

say_hellois now bound to this returnedwrapperfunction. - When

say_hello("Alice")is called, thewrapperfunction executes. - The wrapper prints “Something is happening before…”, then calls the original

say_hellofunction with “Alice”, which prints “Hello, Alice!”. - Finally, the wrapper prints “Something is happening after…” and returns the result from the original function.

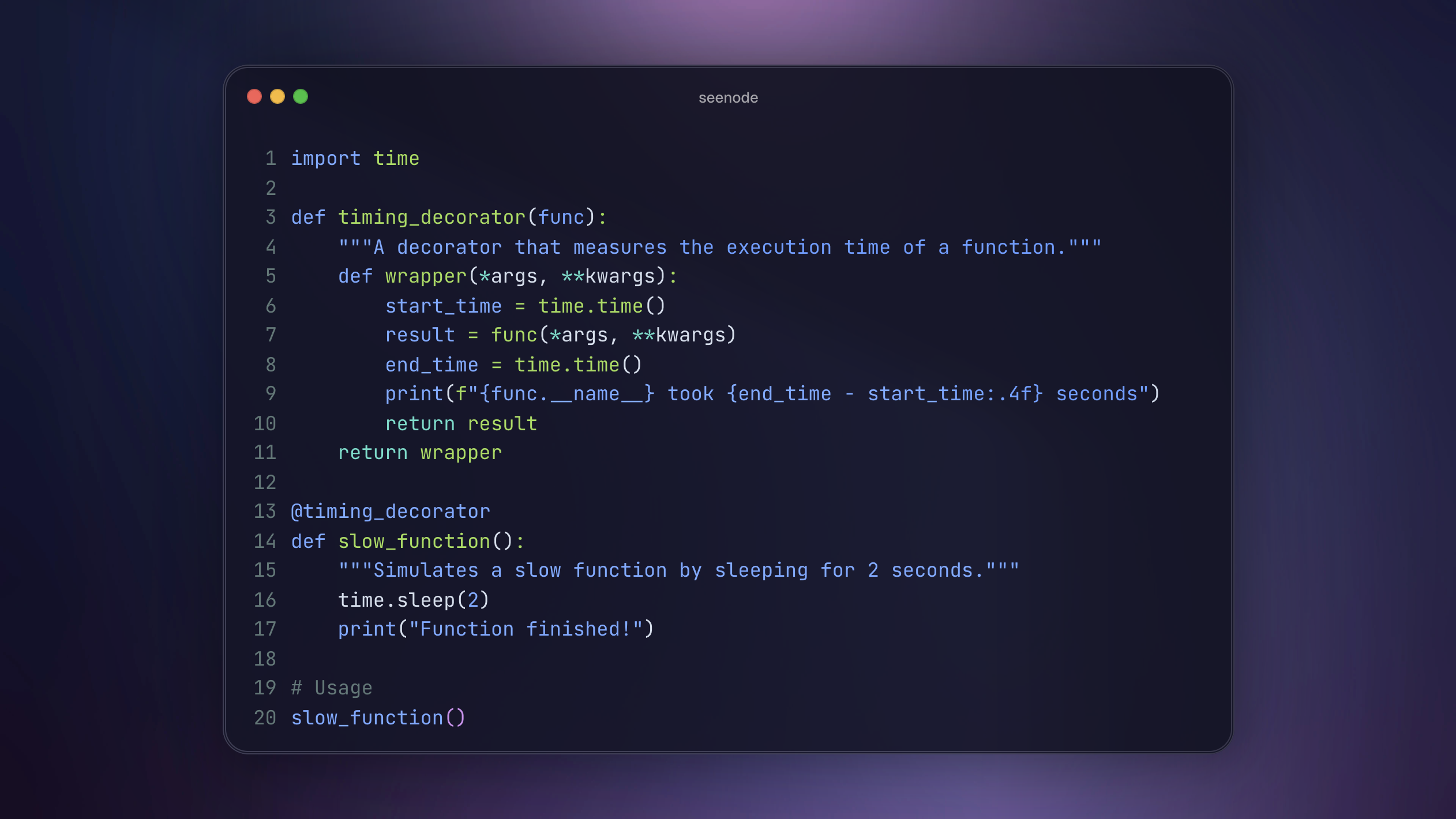

Let’s look at a more practical example: a timer decorator.

import time

import functools

def timer(func):

@functools.wraps(func) # Preserves original function metadata

def wrapper(*args, **kwargs):

start_time = time.perf_counter()

result = func(*args, **kwargs)

end_time = time.perf_counter()

run_time = end_time - start_time

print(f"Finished {func.__name__!r} in {run_time:.4f} secs")

return result

return wrapper

@timer

def slow_function(n):

"""A function that simulates some work."""

time.sleep(n)

return f"Slept for {n} seconds."

print(slow_function(2))

In this timer decorator, we import the time module for timing and functools for a crucial piece of functionality: @functools.wraps(func). This decorator, when applied to the wrapper function, copies the original function’s metadata (like its name, docstring, etc.) to the wrapper. This is *extremely important* for debugging and introspection, as without it, the decorated function would appear to have the name and docstring of the wrapper, which can be very confusing.

The slow_function, decorated with @timer, will now print its execution time before returning its result. Notice how the docstring for slow_function is correctly preserved because of @functools.wraps.

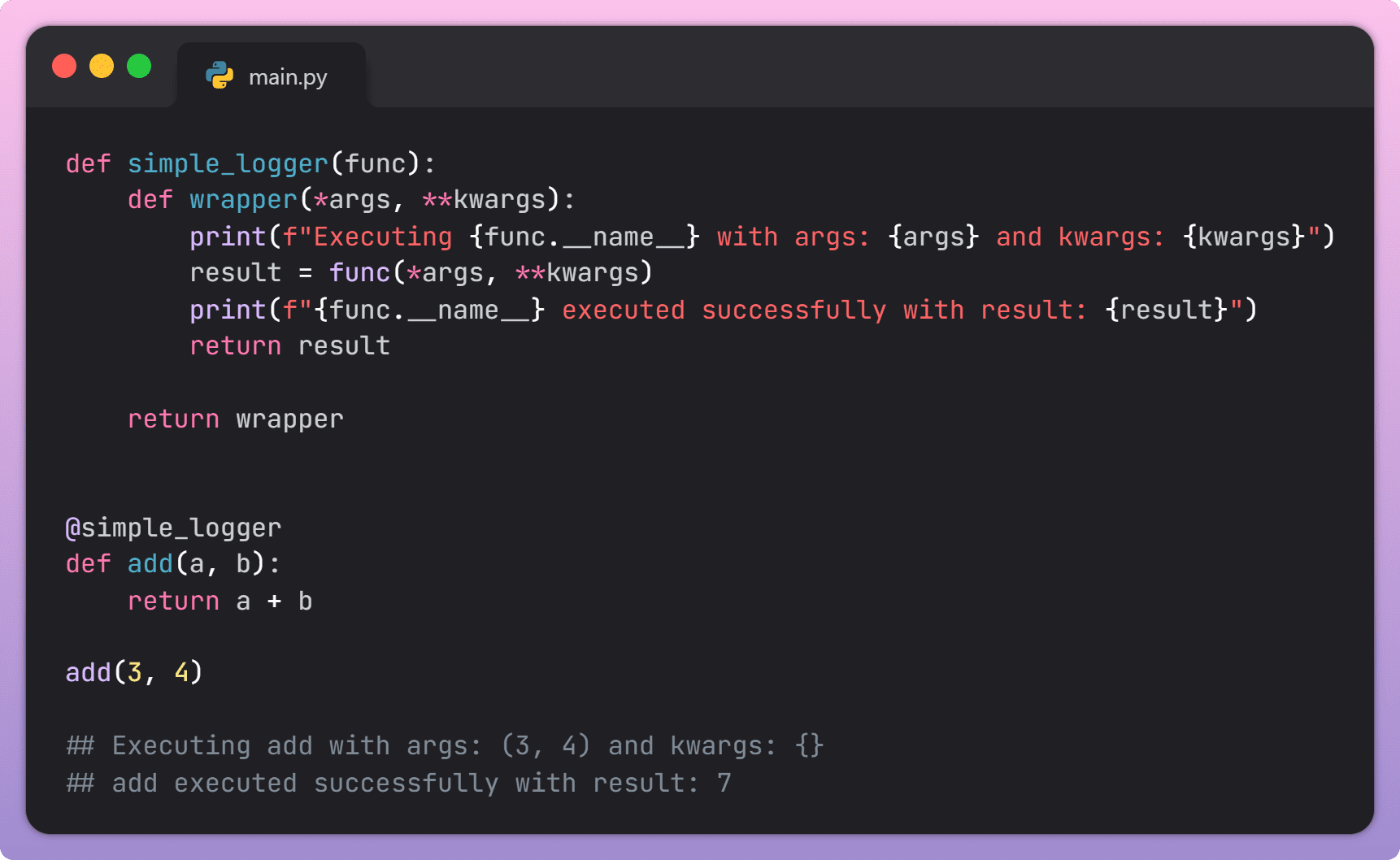

Common use cases for python function decorators include:

- Logging: Tracking function calls, arguments, and return values.

- Access Control: Implementing permissions or authentication checks.

- Input Validation: Ensuring arguments passed to a function are valid.

- Caching/Memoization: Storing results of expensive function calls to avoid redundant computations.

- Timing: Measuring and reporting the performance of functions.

This python decorator tutorial is building a solid foundation for understanding these powerful tools. We’ve covered python function decorators and their fundamental structure.

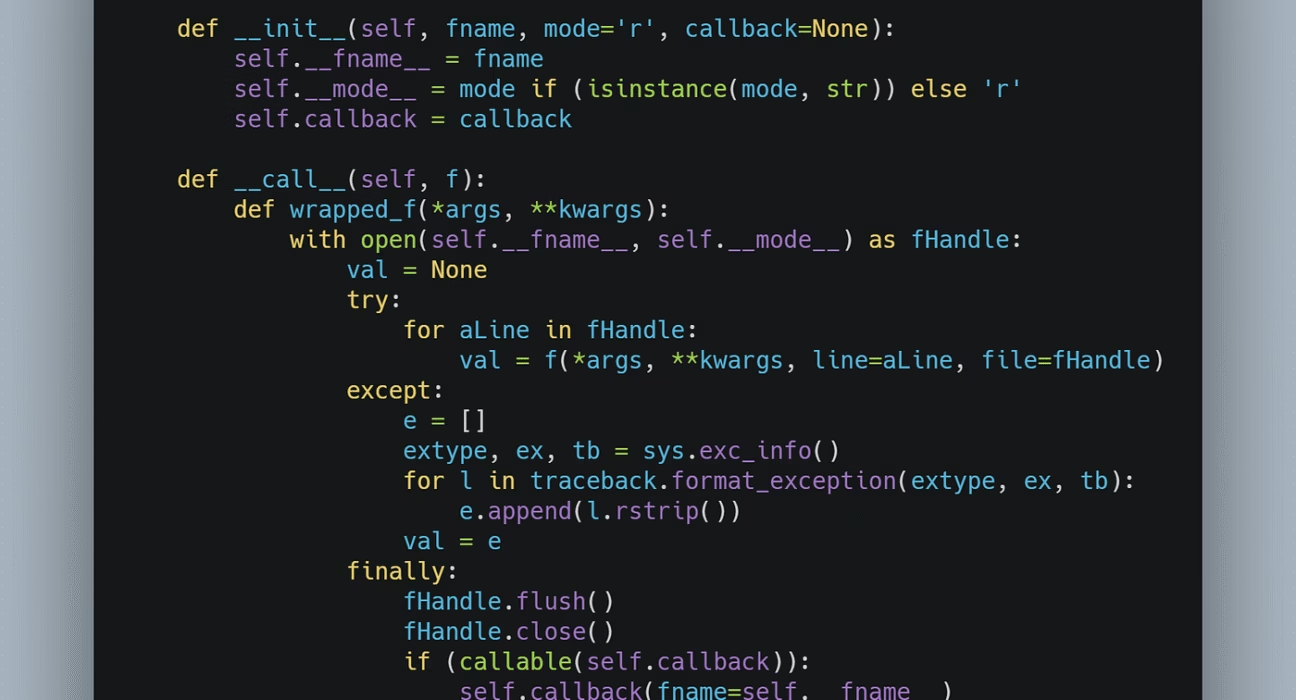

Python Class Decorators

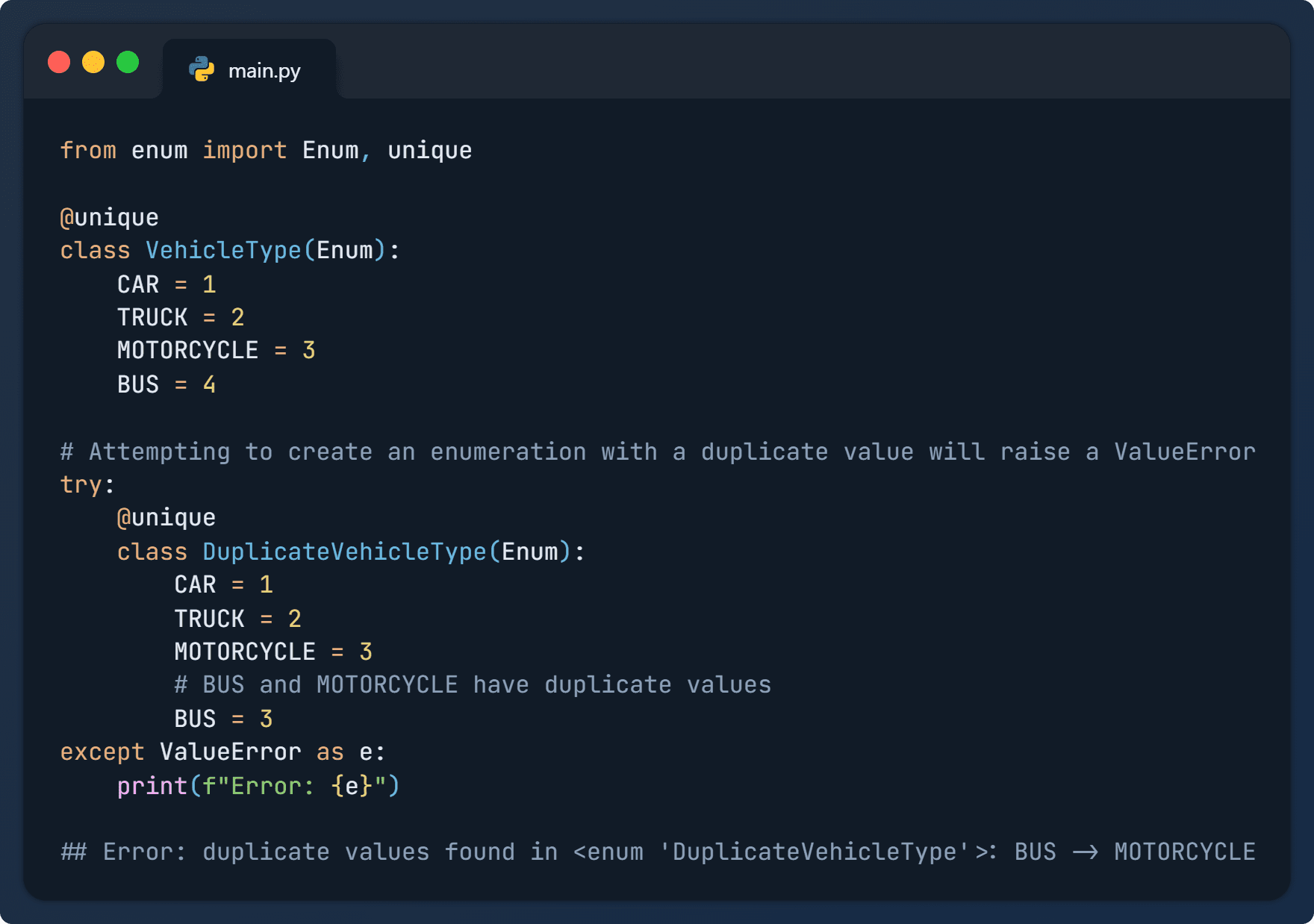

While function decorators are more common, Python also allows for python class decorators. These are decorators that apply to entire classes, modifying or enhancing their behavior. The @ syntax for applying them to a class is identical to how it’s used for functions.

A python class decorator is a function that takes a class as an argument, modifies it in some way, and returns the modified class. Let’s illustrate with an example that adds a welcome message to a class’s __init__ method:

def add_welcome_message(cls):

original_init = cls.__init__

@functools.wraps(original_init)

def new_init(self, *args, **kwargs):

print(f"Welcome to the {cls.__name__} class!")

original_init(self, *args, **kwargs)

cls.__init__ = new_init

return cls

@add_welcome_message

class MyClass:

def __init__(self, value):

self.value = value

print(f"Initialized with value: {self.value}")

obj = MyClass(10)

In this example:

add_welcome_messagetakes the classMyClassas its argument (cls).- It retrieves the original

__init__method. - It defines a

new_initfunction which will effectively replace the original__init__. Thisnew_initprints a welcome message and then calls theoriginal_init. - The class’s

__init__attribute is updated to point tonew_init. - The decorator returns the modified class.

When an instance of MyClass is created, you’ll see the welcome message printed first, followed by the initialization output. (Source: Real Python)

It’s also common to decorate individual methods within a class using function decorators. This allows you to apply specific behaviors (like logging or timing) to methods without altering the class definition extensively.

import time

import functools

def timer(func):

@functools.wraps(func)

def wrapper(*args, **kwargs):

start_time = time.perf_counter()

result = func(*args, **kwargs)

end_time = time.perf_counter()

run_time = end_time - start_time

print(f"Finished {func.__name__!r} in {run_time:.4f} secs")

return result

return wrapper

def debug(func):

@functools.wraps(func)

def wrapper(*args, **kwargs):

args_repr = [repr(a) for a in args]

kwargs_repr = [f"{k}={v!r}" for k, v in kwargs.items()]

signature = ", ".join(args_repr + kwargs_repr)

print(f"Calling {func.__name__}({signature})")

result = func(*args, **kwargs)

print(f"{func.__name__!r} returned {result!r}")

return result

return wrapper

class MyService:

@debug

@timer

def process_data(self, data):

"""Simulates data processing."""

time.sleep(1)

return f"Processed: {data}"

service = MyService()

service.process_data("sample_input")

In this scenario, both the @debug and @timer decorators are applied to the process_data method. When the method is called, these decorators will execute according to their stacking order.

When to use Class Decorators vs. Function Decorators:

- Use class decorators when you need to modify the class itself, its methods collectively, or add class-level attributes. They are less common but useful for framework-level concerns or metaprogramming.

- Use function decorators for modifying the behavior of individual functions or methods. This is the most frequent use case, as it allows for clean separation of concerns like logging, caching, and validation applied to specific pieces of logic.

We’ve now explored python class decorators and how they differ from their functional counterparts.

Decorator Syntax and Application

We’ve touched upon the @ symbol as decorator syntax python, and it’s worth reiterating how elegantly it integrates into Python code. This clean syntax makes it immediately apparent when a function or method’s behavior is being augmented.

One of the most powerful features of decorators is the ability to apply multiple decorators to a single function or method. This is achieved by stacking them vertically, one above the other:

@decorator_one

@decorator_two

def my_function():

pass

This is equivalent to:

def my_function():

pass

my_function = decorator_one(decorator_two(my_function))

(Source: Dev.to)

Crucially, the order of execution when multiple decorators are stacked is from the bottom up. In the example above, decorator_two is applied first to my_function, and then decorator_one is applied to the result of decorator_two(my_function).

Let’s solidify this with a clear code example and step-by-step execution flow:

import functools

def bold(func):

@functools.wraps(func)

def wrapper(*args, **kwargs):

print("Applying bold decorator...")

return f"{func(*args, **kwargs)}"

return wrapper

def italic(func):

@functools.wraps(func)

def wrapper(*args, **kwargs):

print("Applying italic decorator...")

return f"{func(*args, **kwargs)}"

return wrapper

@bold

@italic

def greet(name):

return f"Hello, {name}!"

print(greet("World"))

Execution Breakdown:

- The

greetfunction is first decorated byitalic:greet = italic(greet). The function referred to bygreetis now theitalicwrapper. - Then, the result of that (the

italicwrapper) is decorated bybold:greet = bold(italic(greet)). The function referred to bygreetis now theboldwrapper, which internally calls theitalicwrapper. - When

print(greet("World"))is called:

- The

boldwrapper executes first. It prints “Applying bold decorator…”. - The

boldwrapper then calls its inner function, which is theitalicwrapper. - The

italicwrapper executes. It prints “Applying italic decorator…”. - The

italicwrapper then calls the originalgreetfunction with “World”. - The original

greetfunction returns “Hello, World!”. - The

italicwrapper receives “Hello, World!” and returns"Hello, World!". - The

boldwrapper receives"Hello, World!"and returns"Hello, World!". - Finally, “Hello, World!” is printed to the console.

(Source: Real Python)

Understanding this bottom-up application order is fundamental to correctly implementing and debugging stacked decorators.

Advanced Concepts and Best Practices

As you become more comfortable with decorators, you’ll encounter more advanced scenarios and best practices that can make your code even more robust and flexible.

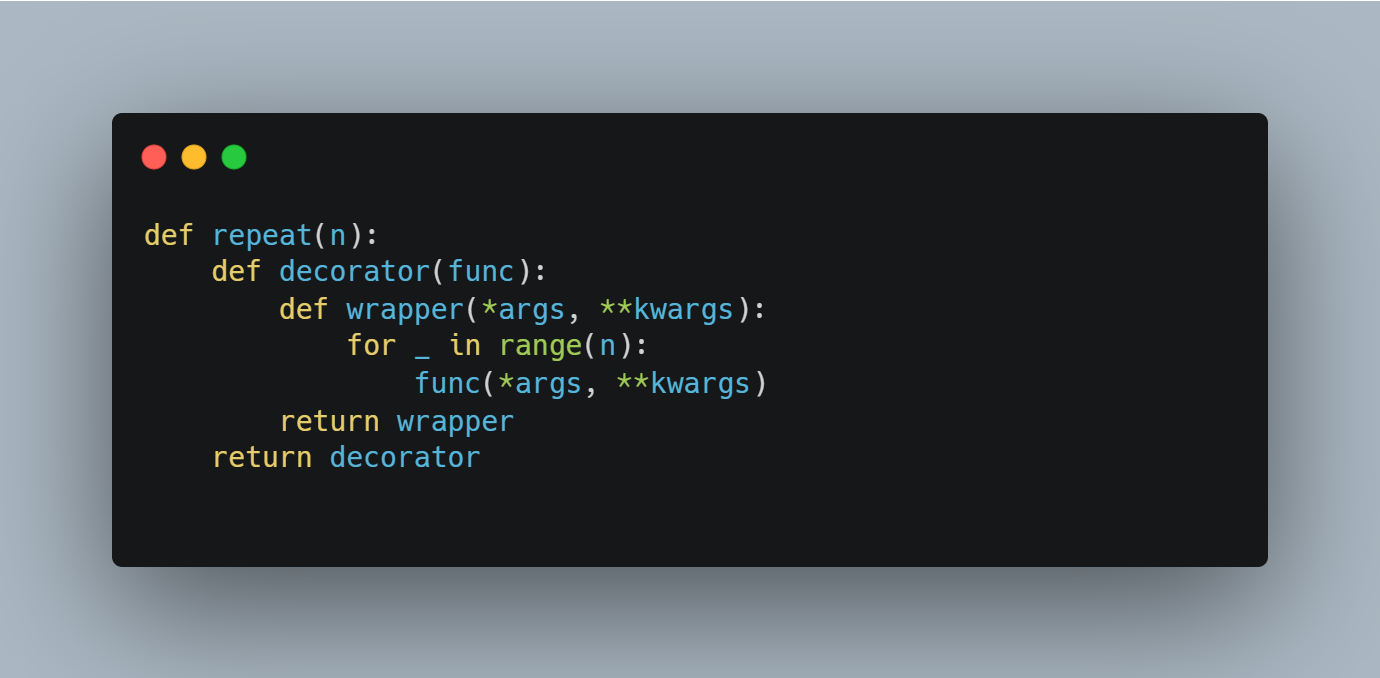

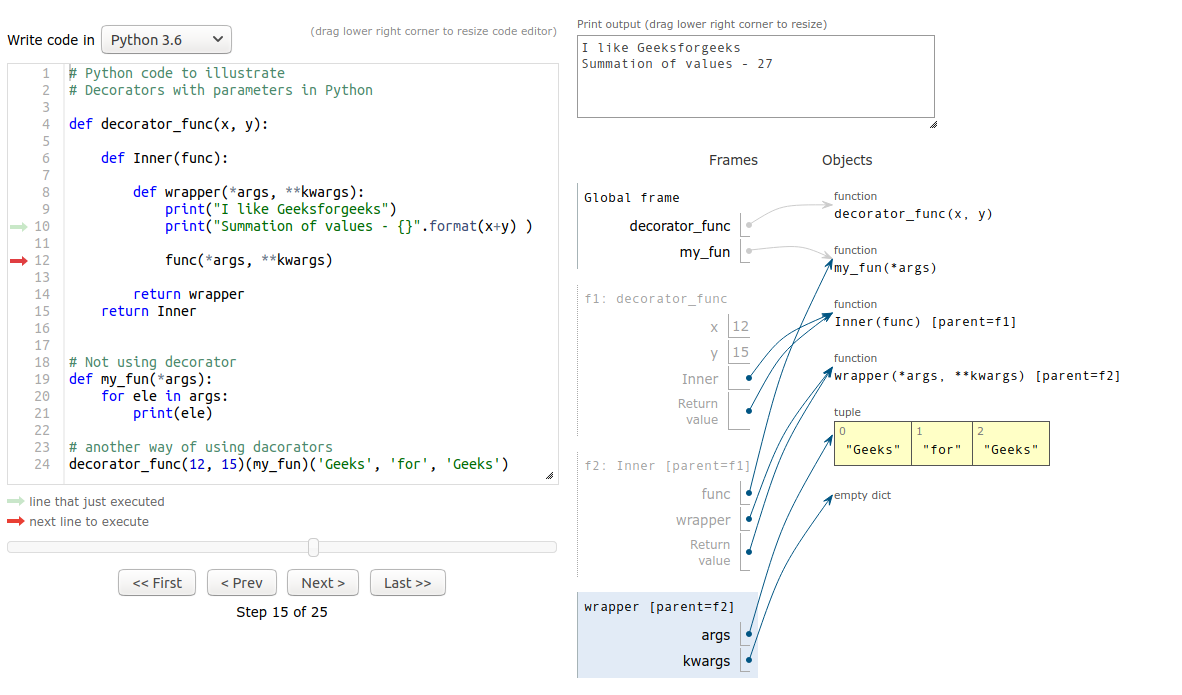

Decorators with Arguments

Sometimes, you need a decorator to be configurable, meaning it should accept arguments. To achieve this, you create a “decorator factory”—a function that accepts the decorator’s arguments and returns the actual decorator function. This results in a three-level nesting:

- The factory function (accepts decorator arguments).

- The decorator function (accepts the original function).

- The wrapper function (adds the behavior and calls the original function).

Here’s an example of a decorator factory for repeating a function’s execution:

import functools

def repeat(num_times): # Factory function

def decorator_repeat(func): # Decorator function

@functools.wraps(func) # Wrapper function

def wrapper(*args, **kwargs):

for _ in range(num_times):

result = func(*args, **kwargs)

return result

return wrapper

return decorator_repeat

@repeat(num_times=3)

def say_whee():

print("Whee!")

say_whee()

Here, repeat(num_times=3) is called first. It returns the decorator_repeat function, which then receives say_whee. Finally, the wrapper is returned and assigned to say_whee. (Source: Real Python)

Using `functools.wraps`

We’ve emphasized this before, but it bears repeating: always use @functools.wraps(func) within your decorators. When you wrap a function, the wrapper function replaces the original function’s identity. Without @functools.wraps, introspection tools, debuggers, and even documentation generators will see the wrapper’s name and docstring instead of the original function’s. This leads to confusion and makes debugging much harder.

Problems without functools.wraps:

function.__name__will show the wrapper’s name (e.g., ‘wrapper’).function.__doc__will show the wrapper’s docstring (often empty or generic).- Help functions (like

help(my_decorated_function)) will show incorrect information.

A clear code snippet demonstrating its correct usage is the timer decorator provided earlier, where @functools.wraps(func) is applied to the wrapper function.

Boilerplate Template

To streamline the creation of robust decorators, here’s a versatile template that incorporates best practices:

import functools

def my_decorator(decorator_args): # Optional: If decorator needs arguments

def decorator(func):

@functools.wraps(func)

def wrapper(*args, **kwargs):

# --- Logic before calling the original function ---

print(f"Decorator args: {decorator_args}") # Example

print(f"Calling function: {func.__name__}")

# -------------------------------------------------

# Call the original function

result = func(*args, **kwargs)

# --- Logic after calling the original function ---

print(f"Function {func.__name__} returned: {result}")

# -------------------------------------------------

return result

return wrapper

# return decorator # Return the decorator if using decorator_args

return wrapper # Return the wrapper directly if no decorator_args

Adapt this template to your specific needs, remembering to include @functools.wraps and handle *args, **kwargs correctly.

(Source: Real Python)

Storing Decorators

As your project grows, you’ll likely create several reusable decorators. To keep your code organized and promote reusability, it’s a best practice to store common decorators in a separate module. Create a file (e.g., decorators.py) and place your decorator functions inside it.

Then, you can easily import and use them in other parts of your project:

# decorators.py

import functools

import time

def timer(func):

@functools.wraps(func)

def wrapper(*args, **kwargs):

start_time = time.perf_counter()

result = func(*args, **kwargs)

end_time = time.perf_counter()

run_time = end_time - start_time

print(f"Finished {func.__name__!r} in {run_time:.4f} secs")

return result

return wrapper

# main_app.py

from decorators import timer

@timer

def calculate_sum(n):

return sum(range(n))

print(calculate_sum(1000000))

This approach enhances modularity and makes it trivial to apply consistent behavior across different functions and classes. (Source: Real Python)

We’ve now covered key advanced concepts for python decorators, including decorators with arguments, the importance of functools.wraps, a boilerplate template, and strategies for storing decorators, all crucial for any serious python decorator tutorial.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What is the primary benefit of using Python decorators?

A1: The primary benefits are improved code readability, maintainability, and reusability. Decorators allow you to separate cross-cutting concerns (like logging, authentication, or timing) from core business logic, making your code cleaner and adhering to the DRY principle.

Q2: Can I apply multiple decorators to a single function? If so, in what order are they executed?

A2: Yes, you can stack multiple decorators vertically. They are applied from the bottom up. The decorator closest to the function definition is applied first, and then the decorator above it is applied to the result of the first decorator, and so on.

Q3: Why is @functools.wraps important in a decorator?

A3: It’s essential for preserving the original function’s metadata (like its name, docstring, and arguments list) onto the wrapper function. Without it, debugging and introspection become difficult, as the decorated function will appear to have the name and documentation of the wrapper.

Q4: What’s the difference between a function decorator and a class decorator?

A4: A function decorator modifies or enhances a function. A class decorator modifies or enhances a class. Function decorators are far more common for adding behavior to methods or standalone functions, while class decorators are used when you need to alter the class definition itself.

Q5: How do I create a decorator that accepts arguments?

A5: You need to create a “decorator factory.” This is a function that takes the decorator’s arguments and returns the actual decorator function. This creates a three-level structure: factory -> decorator -> wrapper.

Q6: Are decorators specific to Python?

A6: While the concept of higher-order functions and code modification exists in many languages, the specific `@` syntax and the way decorators are implemented are unique to Python. Other languages might have similar features like annotations or aspects, but the Python decorator is its own distinct pattern.

“`